Some of Us Have Got to Die

What the 1949 film Twelve O’Clock High still tells us about air combat and the burden of command.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/ca/62ca7f8c-4f49-4862-944e-03fcf53f29d7/06h_on2018_frankarmstrongfranksavagecrewmemberb_live.jpg)

I am not old enough to have seen Twelve O’Clock High in its initial public theatrical release in 1950. The first time I saw this classic end to end was probably in the 1980s, on a scratchy cassette via my tape-eating VHS recorder. It wasn’t what I had expected. I’ve seen it five or six times since—remastered for DVD, through online streaming, and on the old-movie cable channel. It still isn’t what I expect.

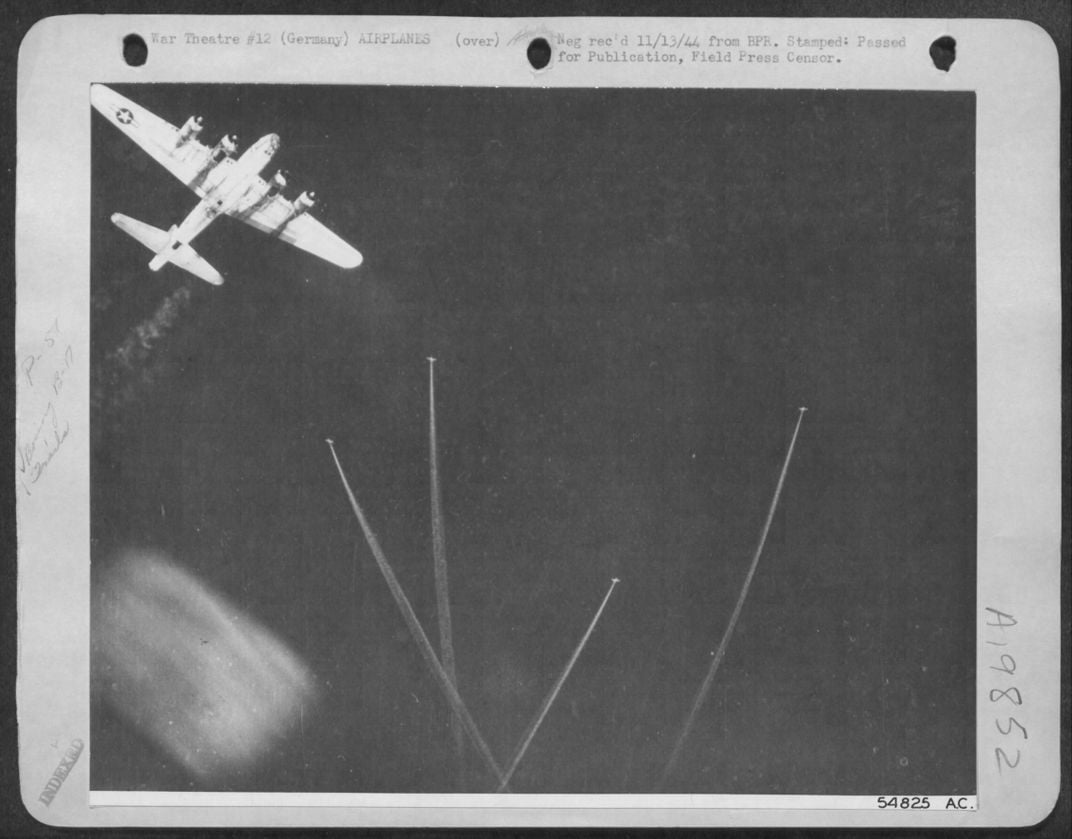

It throws me because I grew up in the cinematic backwash of World War II, a period that produced dozens upon dozens of unmemorable war movies. But Twelve O’Clock High is different, even from the others that have endured on artistic merit. It isn’t a rousing patriotic adventure like Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo or a thoughtful examination of the return to civilian life like The Best Years of Our Lives. It isn’t a satire on the absurdity of war like the Vietnam-era release Catch-22. It’s about an Eighth Air Force B-17 bomb group based in England, but the viewer doesn’t go along on a raid until the last 25 minutes of the picture. There’s aerial combat (including actual footage from American and German gun cameras), but Twelve O’Clock High does not focus on tactics or strategy. Its subject is the brutal psychological cost of warfare.

The story is set during the early days of the American strategic bombing campaign in 1942 and ’43. Without long-range escort fighters and with little combat experience, U.S. Army Air Forces heavy bombers were suffering appalling losses. Based on the wartime experiences of Beirne Lay Jr., a former Eighth Air Force staff officer and bomb group commander, Twelve O’Clock High portrays the crushing weight of command in dire straits.

Most of the drama is on the ground, inside command offices, officers’ quarters, and briefing halls. The climax of the picture takes place in a desk chair, not a cockpit. It was shot in black and white with shadows so stark that it often resembles the noir detective films of the period more than it does other war movies. You can almost smell the tobacco smoke.

The film has lived on in part because of Gregory Peck’s riveting performance as Frank Savage, the pitiless general sent to whip a demoralized Eighth Air Force bomb group into shape. Peck is best remembered today for his role as Atticus Finch, the heroic lawyer (and single parent) of 1965’s To Kill a Mockingbird. When Twelve O’Clock High was in production 16 years earlier, he was just emerging as a major star, but you can see the flinty core of Atticus in General Savage.

The $2 million movie was a success in its day but not a blockbuster, grossing $3.2 million in its first release. It won two Academy Awards, although few would remember Twelve O’Clock High today for winning “Best Sound Recording” of 1950. Where it was a real hit was with the Air Force, which used it for years as a training film in leadership courses. (One of the few objections the Air Force raised with the screenplay was that there was too much drinking. 20th Century Fox agreed to sober it up. So when a shaken character needs steadying, his buddies offer him a smoke, not a brandy.)

At the time of the movie’s release, the newly independent Air Force was dominated by the “bomber generals” of Strategic Air Command—men like Carl Spaatz and Curtis LeMay, themselves commanders in the Mighty Eighth. The SAC top brass admired the film’s endorsement of hard-nosed leadership, which would be essential to Air Force commanders in waging future nuclear warfare, according to John T. Correll, writing in a 2011 issue of Air Force Magazine. As technology and strategies changed along with Air Force command doctrine, Correll wrote, the movie fell out of official use. Still, he declared, Twelve O’Clock High might be “the best movie ever made about the Air Force.”

It is something more than that. Twelve O’Clock High is a memory film that creates a sense of place and time so strong that viewers might believe that they’d been there before through the flashback memories of Harvey Stovall, a supporting character played by Dean Jagger, whose performance won the film’s second Oscar.

That feeling of déjà vu haunted me in 2006, when I went to England in search of the Mighty Eighth.

The Army Air Forces positioned most of its U.K. bomber bases in rural East Anglia, the dead flat, eastern bulge of England that sticks out into the North Sea like a cannon’s mouth aimed at Nazi Europe. My search for the Eighth Air Force had led me to Thorpe Abbotts, the wartime base of the 100th Bomb Group (Heavy). The airfield had been hastily built for the group’s B-17s on prime agricultural land near the town of Diss. Soon after the war ended, the runways, hard stands, and nearly all traces of its military past went back under the plow, but decades later, the local people got permission from the landowner and cooperation from the 100th Bomb Group Veterans Association to restore the still-standing 1942 control tower as a small museum. I’d arranged to meet the volunteer museum keepers there.

Arriving early, I waited at the padlocked gate, admiring the restored tower. Three stories of concrete with a flat roof, steel pipe railings, and a glass box on top for the control room, the tower had recently been repainted an authentic drab Army green.

Author Beirne Lay had been here, flying 10 missions from Thorpe Abbotts with the 100th as an observer for Eighth Air Force commanding officer Major General Ira Eaker. One of those missions was the August 17, 1943, raid on Regensburg. The 100th sent 21 B-17s. Lay flew on Piccadilly Lily, one of only 12 to make it home. (The 100th was one of 16 bomb groups that flew to Regensburg that day; 60 bombers were lost.) More than 50 years later, looking through the gate at the repainted Thorpe Abbotts control tower, I felt as though I’d been here before, not in person but with Jagger’s character, Harvey Stovall.

Though the memories that inspired Twelve O’Clock High belong to Beirne Lay, the movie begins and ends with Jagger, who plays a middle-age ground adjutant in Lay’s barely fictional 918th Bomb Group. The story opens in post-war London, where Stovall, now a civilian, is on business for his Columbus, Ohio law firm. In the window of an antique shop, he spots a Toby jug, a large ceramic mug in the shape of a face. The jug’s face is Robin Hood with a wicked smile and a black eye mask, and it throws Stovall into a swirl of memory. Turning the Robin Hood jug face-out on the mantelpiece in the officers’ club had been the silent signal that the 918th had a mission the following morning.

The Robin Hood jug, a steam train, and a wobbly bicycle take Stovall back to his East Anglia airfield, the base now swallowed up in tall grass. Stovall wanders through the weeds until, in a masterful bit of filmmaking that uses only a swelling music track, a wind machine, and the start-up cough of a B-17 Wright Cyclone engine, he is transported back to 1942. A blast of prop wash flattens the grass around him. A squadron of B-17s, returning from a mission, swoops low, firing flares to summon ambulances for the wounded. A crippled B-17 slides in for a belly landing right in front of the camera, skidding through tents and plowing to a stop in a cloud of dust.

Back in uniform and back in time, Major Stovall goes roaring after it with the rescue party.

I have to remind myself that Jagger was never in the Eighth Air Force or in early-1940s East Anglia. He shot his scenes four years after the war ended, filming on deserted airfields in Alabama and Florida and on sound stages in Hollywood. He’s an actor. Performing on a set. It’s illusion. It’s a movie.

I am not the first to conflate drama and history. Yet Twelve O’Clock High fascinates me precisely because it looks back at a World War II past that was scarcely past when the film was made. The strategic world of the Eighth Air Force that the movie recreates—massive formations of heavy bombers fighting their way to targets—was obsolete by 1949, but the filmmakers arrived in time to achieve authenticity on a budget. The Air Force put a dozen battered but still-flying B-17s (with U.S. Air Force crews) at the disposal of 20th Century Fox. The service also supplied World War II surplus flight gear (including many sought-after A-2 leather flying jackets later reported “lost” by the actors), a technical advisor at no fee, and several hundred airmen as volunteer extras. The studio acquired a surplus B-17 for the crash scene, paying stunt pilot Paul Mantz $2,500—about $26,000 in today’s money—to execute a wheels-up emergency landing for the cameras.

Today, we have computer-generated imagery that can crash realistic-looking B-17s (or spaceships or fire-breathing dragons) for films and video games. In Twelve O’Clock High, as in most war films of the era, those are real B-17s. (A few of them were slightly radioactive, having been used as drones in open-air A-bomb tests.) The filmmakers may be play-acting World War II, but the B-17s in the film are a last operational ghost squadron, a glimpse of a dying age, like a harbor filled with square-rigged sailing ships or a herd of wild buffalo.

Anyone involved in Twelve O’Clock High’s production would likely have been embarrassed by any sissy talk of Art with a capital “A.” Director Henry King is a prime example. Movie historian William Everson says that’s one reason traditional Hollywood studio directors like King have been overlooked by film buffs. “For directors of the past to be rediscovered by contemporary critics, they usually have to have been off-beat, ahead of their time, or even abysmally bad but, at the same time, interesting in a bizarre way,” Everson says. “But King fits into none of these categories. Far from being ahead of his time, he was exactly of his time.”

And this man of his time had little time for Art. “To me,” King told an interviewer in 1979, “motion pictures are less about art than about storytelling.” He’d caught the showbiz bug from theatrical companies barnstorming through rural Virginia at the turn of the 20th century. In 1906, he ran off with the Jolly American Tramp Show to play nine shows a week (six evenings and three matinées) while chugging from small town to small city via milk train.

In 1915, King landed in Los Angeles as a contract actor for the Lublin Manufacturing Company, one of dozens of Hollywood studios in those early frenzied days cranking out silent “three-reelers.” King the film actor soon volunteered to become King the film director even though directors weren’t highly valued. In 1916, King was paid $75 a week for acting and $25 a week for directing.

Henry King never looked back, eventually directing 108 features in a nearly 50-year career that went from “silents to CinemaScope,” as Everson put it. From silent films, King graduated to directing “talkies” at 20th Century Fox, where he became a fixture, knocking out feature after feature for studio chief Darryl F. Zanuck. (Zanuck had a controversial wartime tenure as a colonel in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, covering the U.S. invasion of North Africa before resigning his commission in 1944.)

In early 1949, Zanuck called in King to tell him he had been saving a sensational story just for King. If King didn’t like it, Zanuck said, he’d junk the whole thing. Well, maybe.

According to The 12 [sic] O’Clock High Logbook, a labor of love and a work of determined scholarship by Allan T. Duffin and Paul Matheis, Zanuck had already been working with another director on the project but had just fired him. Duffin and Matheis, who seem to have studied every script draft, every studio memo, and every Air Force directive about the project, said that Zanuck’s interest was genuine. He’d paid $100,000 for screen rights even before Beirne Lay and co-author Sy Bartlett had published Twelve O’Clock High, their novel, in 1948. That was big money then. With Zanuck breathing down their necks, Lay and Bartlett had been writing and rewriting a screenplay for nearly a year before King agreed to direct.

Whether or not King had been Zanuck’s first choice, he was the perfect choice. Known as the “flying director,” King, who’d earned his private pilot’s license in 1918 (and kept it current until a few months before his death at age 91 in 1982), was a tireless advocate of the airplane as an industrial tool for the movie business. For Twelve O’Clock High, King scouted locations in his own Beech Bonanza, moved the cast and crew from location to location in a chartered Douglas DC-4, and gave the ground operations scenes a no-nonsense authenticity.

But it was still a Darryl F. Zanuck production. To get the B-17s and other resources he needed, the hard-charging mogul went straight to Air Force Chief of Staff Hoyt Vandenberg. When at the last minute Eglin Air Force Base refused to hand over a B-17 for the crash-landing scene, Zanuck phoned Vandenberg, who ordered the staff at Eglin to work something out. They delivered a B-17 for crashing but with an agreement that 20th Century Fox would return every scrap of wreckage and pay all transport costs.

Zanuck shaped the story too. The novel had featured an all-too-predictable romance between Savage and a beautiful Royal Air Force flight lieutenant. Zanuck insisted that the romance and anything else that didn’t ratchet up the tension had to go.

When the film was released in 1950, the Fox publicity department promoted it as “A story of twelve men as their women never knew them.” It was no wonder. There was only one female speaking part—a nurse. Lay and Bartlett had boiled down their novel into a screenplay so tightly focused on the internal struggles of the 918th Bomb Group that women and the Luftwaffe itself seem almost irrelevant to the narrative.

Peck, the leading man, was Zanuck’s choice. Though he dominates the film, it’s the character actors around him who give the 918th life. Jagger made a huge sacrifice to get the part of the steel-spectacled Major Stovall. Zanuck badgered him into appearing in the film without his toupee—a first in his career. The supporting cast is filled out with half-familiar Hollywood faces and half-forgotten Hollywood names like Gary Merrill, who is terrific as a stressed-out group commander, and Millard Mitchell, who stands in for the historical Ira Eaker—the lonely Old Man at the Top, ordering young men to fiery deaths.

Despite the caliber of its creators and cast, Twelve O’Clock High still might have been a dud. Good people make bad movies all the time.

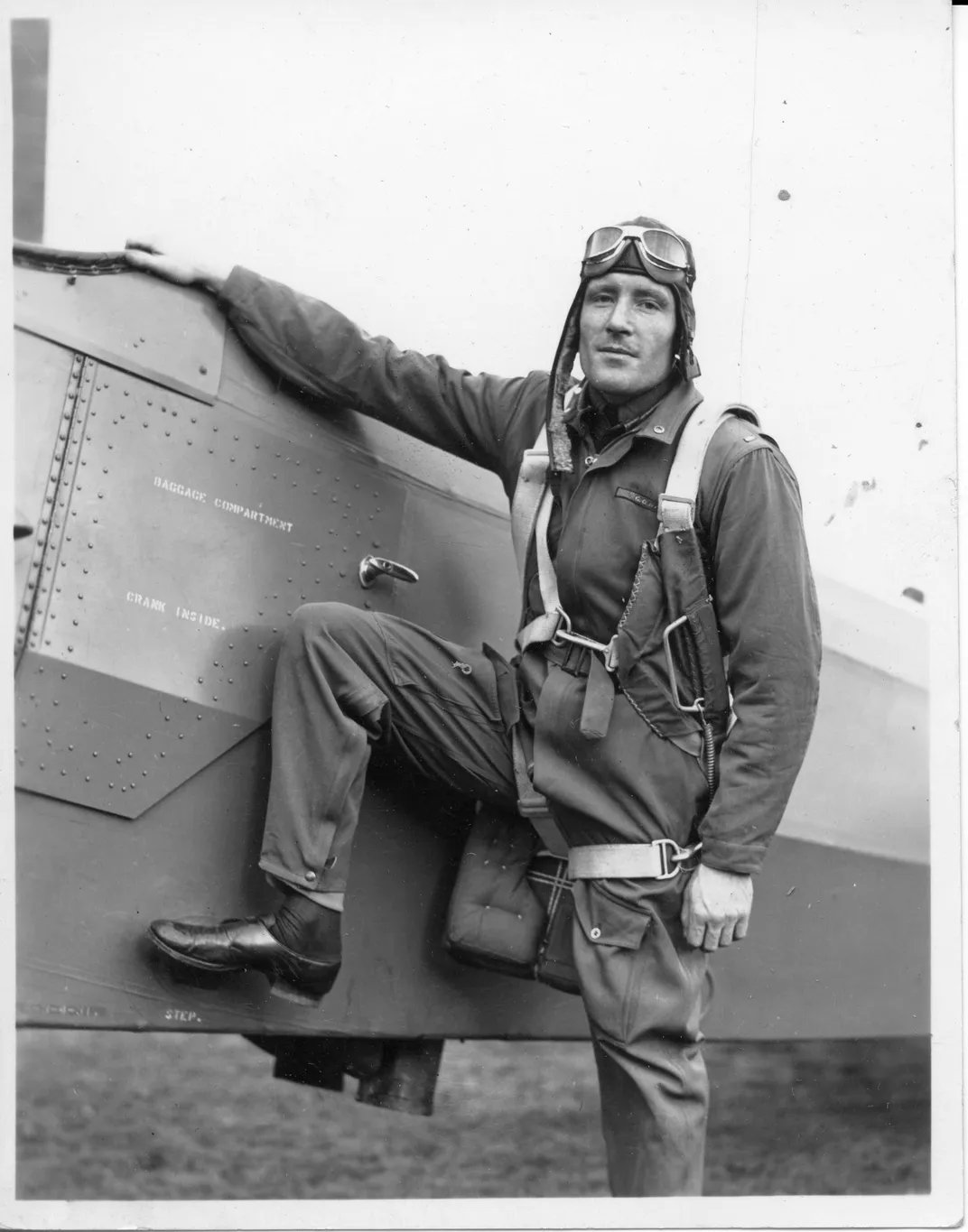

The reason this one came together was Beirne Lay. Drawing on his own wartime experiences, he also took inspiration from historical Army Air Forces figures from General Eaker down to the real-life “stowaway” company clerk who became a crack aerial gunner. His model for General Savage was Colonel Frank A. Armstrong Jr., who in early 1943 was sent by Eaker to shake up the floundering 306th Bomb Group. (The fictional 918th is the real 306th times three.)

Lay had joined the Army Air Corps back in 1932, a year after graduating in English from Yale. In those lean Depression years, Lieutenant Lay was assigned to the Air Corps’ fledgling bomber command, which was flying obsolete two-engine biplanes like the Keystone B-6 and Curtiss B-2. The lieutenant soon took to his typewriter to champion the Air Corps in the press. Aviation editors clamored for Lay’s knowledgeable articles, and Air Corps brass took note of his byline. After finishing his Air Corps active-duty requirement in 1935, he left to edit The Sportsman Pilot. In 1937, his first novel, an account of his Air Corps training called I Wanted Wings, was optioned for the movies by Paramount Pictures but mangled beyond recognition into a 1941 release starring Ray Milland.

By then, Lay was back in the Army Air Corps as a captain seeking a combat assignment. Instead, he was snagged by Eaker, who had closely followed Lay’s writing career. Eaker carried him off to England in early 1942 as the Eighth Air Force communications officer.

Lay was torn. As a key member of Eaker’s inner circle, he had a ringside seat on the bombing war. But as a pilot, his desk taunted him. He begged for a transfer and was finally allowed to “familiarize” himself with the B-17s flown by the 100th Bomb Group at Thorpe Abbotts.

Now a major, Lay arrived in time for the raid on Regensburg. It was murder. More than 550 crewmen were listed as missing after the raid, most of them killed. Many of the bombers that made it back were damaged beyond repair. By the fall of 1943, the Mighty Eighth was close to collapse. Yet after reporting back to Eighth Air Force headquarters, Lay still itched for a combat command.

In 1944, Lay—now a lieutenant colonel—was sent back to the States to stand up a new B-24 bomber group, the 487th Bomb Group (Heavy). He found the job of group commander almost crushing: green pilots, under-trained crews, malfunctioning aircraft. Somehow he moved the group across the Atlantic and prepared them for combat from their base in East Anglia. The responsibility weighed on him. In his quarters at night, Lay stared at the ceiling, unable to forget that many of the young men under his command would soon be either dead or imprisoned across enemy lines. “For a few seconds, I lay there luxuriating in the feel of clean sheets staring at those cryptic letters above my bedroom door: C.O.’s Bedroom,” he wrote. “There were nearly 40 of these rooms on 40 American bomber stations in England and each room harbored a man who carried a heavy load. Many of them must have wondered as I did, if the human mechanism was designed to stand up long under such an ordeal.” That bedroom ceiling and that question would both feature prominently in Twelve O’Clock High.

Lay’s combat career was short. Determined to lead from the front, Lay was shot down in May 1944 on his fourth mission against French targets in preparation for D-Day. Five of his crew died in the crash. Another five bailed out, including Lay who managed to evade capture, take shelter with the French Resistance, and walk into the advancing American lines three months later.

Lay recounted this adventure in his 1945 book, I’ve Had It. (Republished in 1980 under the title Presumed Dead, it’s a great read no matter what you call it.) But by the time he got back to England, the 487th Bomb Group had a new, highly competent commander. Moreover, Lay now knew too much about the French underground for the Air Force to risk the possibility of his being shot down again. He was finished as a combat commander. “I knew that I was swallowing the bitterest disappointment of my life and I would never get over it,” he wrote.

By 1946, Lay was trying his hand again as a civilian screenwriter in Los Angeles when a figure from the recent past, Sy Bartlett, popped up.

Hollywood had been good to Bartlett. Before the war, he had racked up credits, thrown lavish barbecues, and played on Zanuck’s polo team. Once the war began, Bartlett pulled strings to join an Army documentary unit and then more strings to get to England.

One of those strings led him to Beirne Lay. They clicked. Lay introduced Bartlett to Eighth Air Force commander Major General Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, Eaker’s boss at the time. Spaatz took Bartlett on as his personal intelligence assistant. From that lofty perch, Bartlett toured RAF and AAF bases at will, rode along on bombing missions, and nearly got himself court-martialed for calling a press conference at Claridge’s Hotel in London to describe his personal role in an RAF night raid on Berlin.

After the war, Bartlett found Lay in Hollywood, convinced that collaboration on an Eighth Air Force story would make for a dynamite novel and an even more lucrative screenplay.

Lay resisted. Bartlett persisted. Finally Lay retired to the basement of his overcrowded apartment building and, with a portable typewriter parked on an orange crate and a naked light bulb overhead, started writing. Bartlett would do his part, shaping the plot and honing the dialog, but the spine of Twelve O’Clock High sprang from Lay’s vivid recall of the weight of command.

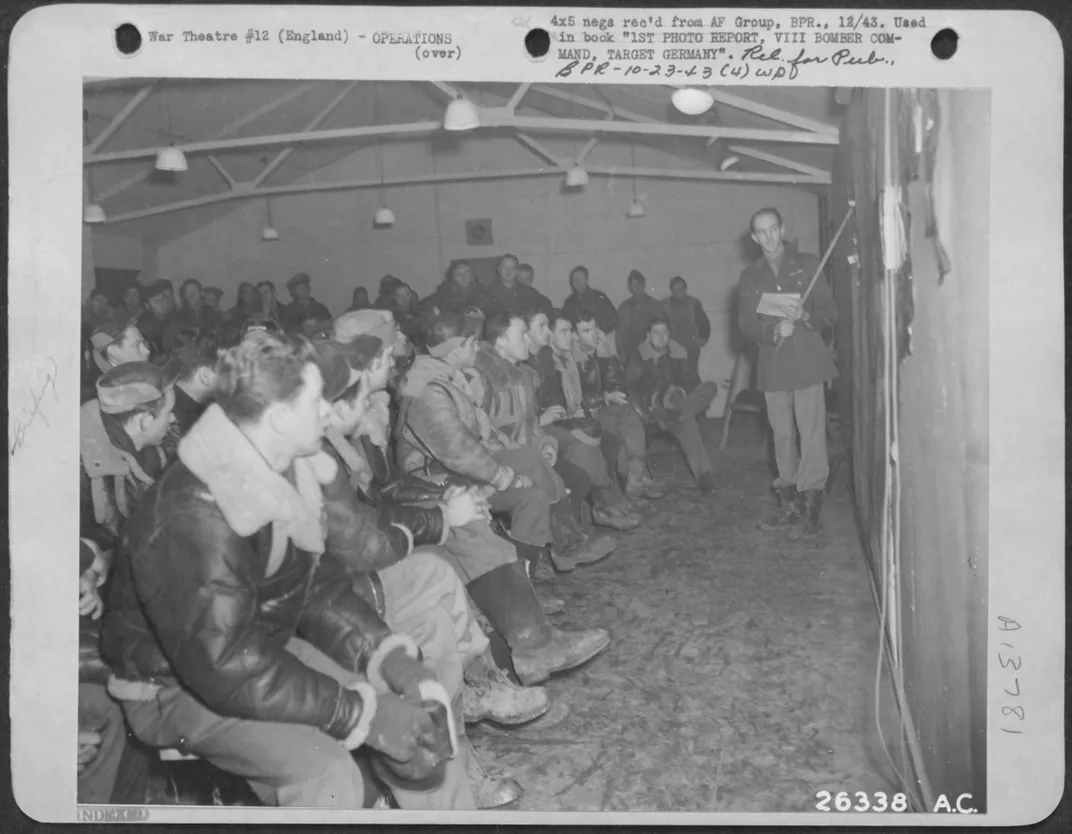

That’s most clearly dramatized in the film when General Savage gives his first speech to the flight crews of the 918th assembled in the briefing hall. To a man, they hate his guts. He’s just pushed aside their old commander. He lands on them like a ton of bricks, dressing them down as slackers and whiners. “We’ve got to fight. And some of us have got to die,” he tells them. “Consider yourselves already dead. After that, it won’t be so tough.”

This is not an inspirational pep talk. It’s not chest beating. It’s not poetry. It isn’t pretty. But it’s what faced the Eighth Air Force in East Anglia in summer 1943. If you weren’t there, you don’t know. But watching Twelve O’Clock High, you can be, all over again.