In 1940s Burma, a New Kind of Flying Machine Joined the War: The Helicopter

Toward the end of WW2, the strange new craft became vital in guerrilla warfare.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7d/60/7d60fd16-cbe7-48f8-96e9-ac6f07b369df/04b_aug2019_harmanandyr4b_live.jpg)

Few people had seen one in the fall of 1943 or would have known what it was if they had. But shortly after a prototype impressed official U.S. Army Air Forces officials at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, the helicopter became part of an unconventional strategy to defeat the Japanese in Burma. Its first call to military service came when U.S. Army Air Forces Lieutenant Colonel John Alison went to Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio to find out what a helicopter could do.

By the time of his 1943 Dayton visit, Alison was already an ace. Flying Curtiss P-40s and leading the 75th Fighter Squadron—part of a task force commanded by General Claire Chennault after his fabled American Volunteer Group had disbanded—Alison came to the attention of Army Air Forces Chief Henry “Hap” Arnold. Arnold, who was constantly devising new ways to use airpower, enlisted Alison and his friend Phil Cochran in a Top Secret project. Both Alison and Cochran had built reputations as daring leaders who improvised when traditional tactics failed. Alison had won a Distinguished Service Cross for an experimental night interdiction flight in China. In a series of interviews in 2001, I talked with Alison about his Air Force career (he died in 2011 at 98, having earned the rank of major general before he retired) and about his partnership with Cochran, a friend of cartoonist Milton Caniff and the inspiration for the character Flip Corkin, a flight instructor in the popular Terry and the Pirates comic strip. Cochran, who led hit-and-run attacks from Tunisia on Axis forces, was once described by the journalist Vincent Sheean, who served in North Africa, as “a kind of electrical disturbance in human form.” These were the two pilots Arnold selected to build the first U.S. group of Air Commandos, a term he coined for pilots who would insert, supply, protect, and extract ground forces in the Burmese jungle, deep behind enemy lines.

Of the two, Alison was the more diplomatic, but his attempts at negotiation with a manager at Wright Field were initially unsuccessful. He remembered trying to persuade the program officer to sign over several of the Sikorsky YR-4s the Army was testing there. “We need six of these,” he said. The manager, he recalled, said “no.”

“You can’t have them,” he told Alison. “They’re not ready for real world conditions. The rotor blades are laminated, wood pieces glued together. In the hot climate you want to take them to, they’re liable to come apart. There’s just so much we don’t know about them.”

Alison thought about that. “Well, the mission we’re going on will be pretty dramatic,” he said. “We can take six of your helicopters and your testing gear to India and test them in real conditions. Then we’ll go rescue some people in the jungle who are in real trouble. That will get Sikorsky great publicity.” The manager was not moved, and Alison went back to Washington empty-handed.

Cochran, in the meantime, newly returned from North Africa, traveled to Britain to meet the commander of the Special Force, a controversial British irregular warfare expert, Orde Wingate. Wingate had recently returned from a punishing guerrilla raid into Burma, though his irregular forces had managed to penetrate 200 miles into the jungle.

It took Alison and Cochran about a month to establish their air commando unit and its armada of more than 300 aircraft: among them, 13 C-47 transports and 150 gliders to fly the Chindits, as Wingate called his guerrilla fighters, and their mules into the jungles of Burma. A squadron of 30 P-51A fighters and 13 B-25 Mitchell bombers would be the artillery for the ground troops; a light airplane force of 100 Stinson L-5 Sentinels and 20 Stinson L-1 Vigilants would fly the wounded back to India. They weren’t sure where the helicopters fit in, but they were confident in Arnold’s support. Alison recalled: “We had a secret weapon: wrote up our memorandum, signed it General Barney Giles. Giles allocated resources for Arnold.” Alison knew he had the protection of the Chief of the Army Air Forces in case anybody questioned the signature. “Nobody questioned us,” he said, adding that Arnold’s approach was: “Damn the paperwork, get out there and fight!”

In the end it took a conference where Alison had to convince a panel of generals that the helicopters were necessary at a time when no one really knew much about how helicopters could be used.

The Sikorsky that Alison got was designated the YR-4B, the “Y” meaning it was still in “service test,” and the “B” that it had 20 horsepower more than the original model. It was built of fabric-covered steel tubes; “a shoebox with windows,” somebody called it; its 200-horsepower, seven-cylinder Warner 500 radial engine was installed in the rear of the cabin. Theoretically, the YR-4B could carry a pilot and passenger at 65 mph for about 100 miles. High heat and humidity would affect its performance significantly.

The air commando unit started moving their aircraft and more than 500 personnel to India in November 1943. (The following year, it was designated the 1st Air Commando Group.) Each of the six helicopters went in its own Curtiss C-46. “The first one to almost reach us was in a C-46 that crashed in a thunderstorm about 60 miles from its destination,” said Alison. That helicopter was destroyed and its pilot was killed. Another helicopter arrived without a tail rotor. “The rotor was put on another C-46 that went somewhere else,” said Alison. “It took us two months to find it. The people who received it wondered What the hell is this? They had never seen a tail rotor before.”

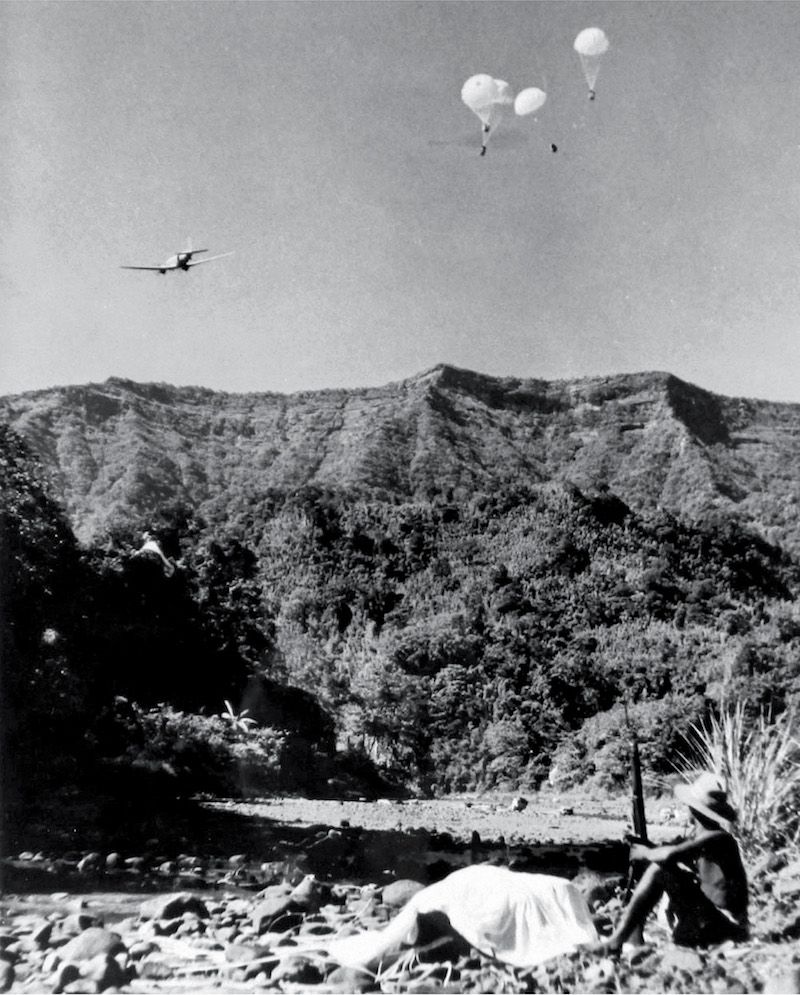

On March 5, 1944, under a full moon, 61 Air Commando GC-4A gliders towed by C-47 Dakotas lifted the first element of the British Special Force Chindits into central Burma. Thirty-five of the gliders and 350 Chindits made it to the jungle clearing they ironically named “Broadway.” The first order of business was to build a landing strip with a bulldozer that arrived in one of the gliders. Completed that night, the strip made it possible for 64 more C-47s to insert more troops. Each night over the next few nights, 100 Dakotas landed. By March 10, 9,000 troops and 1,100 mules and horses had been delivered. With the close air support of Air Commando P-51A fighters and B-25 bombers, the Chindits began taking on the Japanese army. The Air Commando light airplane force of L-1s and L-5s transported injured and wounded troops back to India, dropped supplies to mobile columns, and spotted targets for the soldiers on the ground.

“When we got the Air Commando into the jungle, the fighting we were doing was 150 miles behind Japanese lines,” said Alison. “[The] helicopters wouldn’t go 150 miles. To get to our airfield in the jungle, the helicopter pilot had to stack the passenger seat with tins of petrol, fly half way, and then find an open area and land to refuel. The local Burmese would spot him right away, and then they would try to run out to him.” Because Commandos feared drawing the attention of Japanese troops, they discouraged the curious villagers from approaching what must have been to them a wondrous sight. “We had six P-51s overhead,” recalled Alison. “They would have to strafe out in front of the running villagers, and the villagers would stop and turn back.”

For a time, the helicopters were not called on for rescues. The light airplane force carried out evacuations and other duties very effectively on landing strips—usually a smoothed-out rice field—that were often shorter than the 900 feet specified for the Stinsons. Then on April 21, 1944, an L-1 Vigilant carrying three wounded British soldiers was hit by ground fire and crashed in a rice paddy. All four men in the airplane made it into thick jungle as Japanese troops closed in. Having spent much of my life poking around Southeast Asia, I’ve learned that the Burmese jungle can be hard to penetrate. It must have been a good hiding place. Nevertheless, an Air Commando L-5 spotted the small group from the air, then found the only place nearby where a light airplane could land: a sandbar on a river. But the injured men could not reach the river on their own. The call went out to send in the “eggbeater.”

Carter Harman had been an Army Air Corps biplane instructor before volunteering to fly helicopters. In India barely a month when the L-1 went down, he was instructed to fly from India’s Lalaghat airfield to Taro in northern Burma, 600 miles of jungle with a 5,000-foot mountain in the way, right at the ceiling of the YR-4B. Harman stripped his YR-4B of excess weight, loaded four jerry cans of fuel, and set out. At Taro he was told to fly on to the Chindit base called Aberdeen, another 125 miles south. He reached it on April 25.

At Aberdeen Harman was briefed on his mission. Four men needing rescue were hiding in thick jungle near a clearing believed big enough to land the YR-4B. Because the helicopter could carry only one passenger, Harman would have to make four trips from clearing to sandbar. From there, L-5s would carry the wounded to Aberdeen.

Harman rendezvoused on the sandbar with an L-5, which led him to the clearing near where the three injured troops and their L-1 pilot were hidden. The L-1 pilot, an Air Commando named Ed Hladovcak “went crazy when he saw [the] eggbeater,” Harman reported, according to Robert Dorr’s 2005 history Chopper. He may not have seen one before, but he recognized it as salvation. The most seriously injured Chindit was loaded aboard, and Harman took off, the YR-4B straining and vibrating in the jungle heat. Harman landed on the sandbar, transferred the Chindit to an L-5, and returned to the jungle.

He picked up a second Chindit and brought him to the sandbar. As he landed, the helicopter’s engine cut out: It had overheated and would not start again. Harman had to spend the night on the sandbar, worrying that his day’s activity would lead the Japanese to him, or to the clearing where Hladovcak and the remaining Chindit waited.

Morning came, and the cooled-down helicopter engine started right away. Harman flew to the clearing and brought back the third Chindit. Then he went back for Hladovcak. On approaching the clearing, Harman saw soldiers breaking out of the jungle, about 1,000 feet away, waving rifles. Hladovcak climbed aboard quickly, and Harman climbed to an altitude above the range of rifle fire. But the chopper threatened to seize again, and sank back toward the jungle. After a few tense moments, Harman managed to get full power and climbed away. The men waving rifles below made history’s first helicopter rescue dramatic, but back at Aberdeen, Harman learned that “we were escaping from our own guys.” The riflemen were Chindits; they had broken into the area intent on rescuing their own.

The YR-4B’s rescue of four men from under the nose of the Japanese army showed what a helicopter could do. Harman stayed on in Burma to rescue injured soldiers. John Alison recalled that Air Commandos flew 20 more rescues before their helicopters wore out. Several other YR-4Bs were used in rescues by U.S. forces in other areas before the war ended, but it was only in Burma that they were used in combat conditions.

Harman Carter was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his helicopter rescue flights. After the war, he returned to his career as a music critic for the New York Times, and later Time magazine. He also achieved success as a composer and music industry executive. And the helicopter went on to become indispensable and the most versatile aircraft in military and civilian operations.